A Moment with Álvaro

A Moment with Alvaro

In a few weeks, before the heavy wet season rains return to the Osa peninsula, some friends and family of Alvaro will gather at the base of a mighty Ajo (Caryocar costaricense) tree near the Piro river. Ajos are exceptionally big trees with dense wood. Their rambling thick buttresses lend them the aspect of some fantastical artistic creation. Closely related Amazonian species of Caryocar have ages measuring in excess of 1000 years. The dominance of immense Ajos in the old growth forests in the Osa speak to its deeply pristine past. At the base of one particularly large Ajo tree is a modest plaque honoring Alvaro’s contributions to the conservation of the Osa forests that he loved. There, as he wished, his ashes will be scattered. There could be no better monument to this man so loved by so many so far and wide.

When the first rains fall, the scattered salts of Alvaro will dissolve and seep into the leaf litter. Almost immediately, the delicate white tendrils of fungi will absorb them. Those nutrients will be pumped into the Ajo tree as the roots trade sugars for minerals to their intertwined partner fungi. Soon the ions of Alvaro will be riding in a heavenward flow of sap up into the leafy canopy of one of the mightiest rain forest trees seen on this Earth.

When the Ajo tree bursts into flower, opening golden blossoms that smell just like sautéed garlic, Alvaro will be there in the nectar. Clouds of bats will drink that nectar and they will carry those elements of Alvaro far and wide. All night long foraging bats will void his essence onto orchids, bromeliads, ferns, vines and onto the algae that green the fur of sleeping sloths. In turn these plants will reabsorb the nutrients. Again and again Alvaro will be broadcast deeper into the forest he treasured.

On the day that Alvaro had his Ajo tree dedication he wanted to invite some guests for the ceremony. He did not choose from the array of dignitaries, the presidents and ministers that he knew. He invited local park guards. He put on his old park uniform. He walked arm in arm with his underOpaid underOappreciated posse who is the front line of defense for the forest. It was a time of great emotion for him and as the plaque was unveiled he was beside himself laughing and crying simultaneously. That moment held all the infectious essence of AlvaroOO the kindly father of Corcovado, the inspirational soul of conservation in Costa Rica, the vulnerable child as a venerable man.

When it came time for him to say a few words he struggled for composure, exclaiming, “I just can’t stop crying. I am so gay!” It was one of those selfOdeprecating, touching jokes based on the truth. Alvaro was openly gay. That’s still a very hard thing to be in much of Latin American and the world. But Alvaro would not hide who he was or what he thought. He would say the same words, he would laugh and he would cry in the company of presidents or in the presence of paupers. It was that emotional honesty and brave vulnerability that drew thousands close to him. Alvaro is mourned by so many, not so much because of his great conservation accomplishments, but because he opened his heart to people from all walks of life.

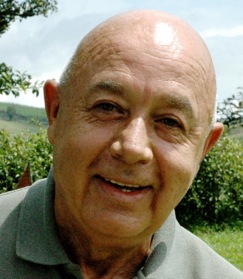

Over the decades Alvaro lost his hair and became rounded, BuddhaOlike in appearance. He was reflective. He was ill. “Friends” took advantage of his generosity and left him poor. He thought about the end and the meaning of his life. But he was emphatically not BuddhaOlike, withdrawing and accepting of Fate. He was very much of and in this troubled, beautiful world and fighting hard for it. On the last day of his life he was campaigning, haranguing the government of Costa Rica to do more to remove illegal gold miners from Corcovado national park, to help the park guards do their work. On every day and on his last day Alvaro defined “commitment”.

How shall we honor such a man and his work? We can offer more than a memorial service or a tribute. Alvaro wanted greater grassroots engagement in conservation. To this end, with the generous support of Diane Edgerton Miller of blue moon fund we are creating The Alvaro Fund, a scholarship fund to engage young people in conservation in Osa. The scholarships will enable young people to work side by side and learn with conservation biologists, park guards, environmental educators, and community activists O anyone trying to safeguard the future of Osa that Alvaro so loved. Some of those young people will begin to believe that they too can be part of the natural magic of Osa. And Alvaro will then be living on in them.

And we can do something more immediate. Alvaro was campaigning to remove illegal gold miners from Corcovado National Park and to reduce the illegal poaching of wildlife in Osa. There is, as of this moment, now a Campaign for Corcovado, a fund that will assist the park staff and civil society in the healing of Corcovado, the park that meant the most to Alvaro.

If you would like to support The Alvaro Fund, or The Campaign for Corcovado or just want to visit Alvaro’s Ajo Tree, to rejoice in remembering his life and to spend a moment with his legacy in that special place, then please write me at adrianforsyth@gmail.com

Sincerely, Adrian Forsyth, CoOfounder Osa Conservation, VP blue moon fund